Archive for the ‘programming’ Category

This interview with the University of Nottingham’s Louise Brown is part of my series of interviews on the new cohort of EPSRC Research Software Engineering Fellows.

Could you tell us a little about yourself and how you became a Research Software Engineer?

I’ve had a peculiar career path. I’ve worked as a software engineer for 25 years. I did my PhD in Mechanical Engineering and then moved to a CS department where I worked for a company whilst based in the Drawing Recognition Research Group. I was working on CAD systems for industrial embroidery machines implementing algorithms for automatically converting image data into embroidery machine input data. I worked there for four years until my daughter was born after which I returned part time.

My daughter was ill when she was small and when my son was born 2 years later, I stopped work completely for 2 years. I then worked part time from home for 13 years, firstly on ‘Easy Cross’ software for design of home needlecrafts. I designed and developed add-on modules for different crafts including bobbin lace making, patchwork and knitwear design. My second job during that time was working on a system for automatic reading of travel documents such as passports and air tickets.

I moved to my current post six years ago which advertised for an open-source software co-ordinator. The job entails running the TexGen project, working as a software engineer but with a Research Fellow job title. After a while I started to become aware of the issues surrounding being employed as a researcher but spending most of the time programming. For me the main issue was the lack of career progression, being employed at the top of the Research Fellow scale but with little chance of promotion because there was limited chance of fulfilling the criteria for Senior Research Fellow. (The fellowship fixed this!).

To try and address this I started doing some teaching (MATLAB course for postgrads and first year undergrad drawing and design tutorials). I also joined committees to attempt to broaden my work profile. I am a co-author on a few papers but not enough for academic promotion, although there is more effort being made now to include me when a specific piece of development has been carried out which enables the work described in the paper. I applied for a promotion last year but was turned down, mainly due to lack of publications but also due to my not having done any PhD supervision..

One problem was that my performance reviewer did not know what to suggest in order to move my career forward. One possibility which I was encouraged to look at was fellowships but, having returned to academia relatively recently, I came into the category of ‘Early Career’ fellowships. These normally specify a time limit since completion of a PhD and the 25 years since I completed made these unsuitable. This fellowship was suitable because despite being labeled ‘Early Career’, it had no such time limits and it didn’t matter that I don’t fit the normal early career pigeon holes.

What do you think is the role of a Research Software Engineer? Is it different from a ‘normal’ researcher?

The fundamental difference is the fact that I do work which underpins research and without which the research wouldn’t happen but isn’t necessarily publishable in its own right. Without the work carried out by the Research Software Engineer the papers wouldn’t get published but they don’t necessarily get the credit. The research gets the publication and the credit!

I often end up spending time doing lots of odds and ends that are significant in that they support researchers and facilitate research but aren’t really quantifiable in the sense of a research output.

The outputs of a RSE are different to a ‘normal’ researcher. For example, in performance review, the work done on outputting software isn’t one of the KPIs. I don’t fit the normal ‘money-in, papers-out’ model of many academics.

You’ve recently won an EPSRC RSE Fellowship – congratulations! Can you give a brief overview of your project?

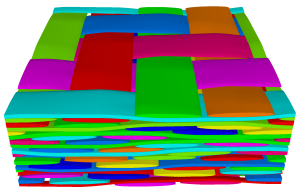

The project is centred around TexGen software. This is open source software for generating 3D geometric models of textiles and textile composites The initial part of the project will be to develop a new major version of the software aimed at addressing the modelling requirements of the increasingly complex textiles and preforms used in composite materials. The project will identify new and emerging areas in textile technology and develop tools to meet the analysis needs of these new technologies and materials.

The Faculty have committed to fund a PhD student and a project has been proposed to research optimisation of 3D woven preforms with various cross-sectional shapes.

Also included in the proposal are elements surrounding programming education and outreach. I currently teach a MATLAB course for postgraduate students which is intended to be a conversion from other languages. The reality is that many of the students haven’t programmed before so the course could be split to better meet the needs of the varying requirements of the students.

How long did it take you to write your Fellowship application?

It was horrendous! It was really hard work. The Business development team in the Faculty were really helpful, giving very useful advice on how to write a proposal. It consumed all of my time for the weeks between acceptance of the intent to submit and the submission date.

One thing that really helped was that two weeks before the submission date, the Graduate School held a ‘Writing retreat’ – 3 days for research staff to ‘just write’. There was space set aside, refreshments, speakers/courses if you wanted them and one-to-one appointments available with a careers advisor and EndNote specialist. The research development team people came down for a couple of meetings but there was a no phones rule and we were encouraged to turn our email off.

Having academics who were willing to spend time reading (and rereading!) the proposal was really important, especially as it was the first proposal that I’d written. The first draft was shredded by one of them but in a way that was very positive.

Who are your project partners?

I don’t have any named on the proposal. For the last couple of years I have been a platform fellow for EPSRC Centre for Innovative Manufacturing in Composites (CIMComp) which has a large number of project partners, funding research projects underpinned by TexGen. It is anticipated that this collaboration will continue. Part of the aim of the project is also to seek out new project partners, particularly for areas of textile research other than composites.

Tell me about your RSE group.

We don’t have one at Nottingham! It’s just me. There are plans to identify other RSEs in the faculty to start building a community. Watch this space.

Which programming languages and technologies do you regularly use?

TexGen is written in C++ and has Python wrappers. A bit of MATLAB for teaching. OS – Windows. I work in Visual Studio and am comfortable in it.

TexGen is cross platform so I have to make sure it builds in Linux. It also makes use of open source libraries such as wxWidgets, SWIG, OpenCASCADE and VTK.

I tend to work on a ‘need to know’ basis, looking for new technologies when there’s a specific need. When you are the only person in a project, you don’t have the luxury of learning lots of technologies.

Are there any languages/technologies that you used to use a lot but have now moved away from? Why?

I used to use C but rarely use it anymore. I also did assembler many years ago. When I was an undergrad, I did a software engineering course that used PDP-11 assembler. It was the first time that the lecturer had taught the course and was incomprehensible! I got the textbooks out of the library and worked my way through them, discovering how much I enjoyed assembler programming in the process. On the back of that the lecturer invited me to do a PhD where I designed and built a filament winding machine. The control system was run from a PC using 286 assembler.

Is there anything on your ‘to-learn’ list?

Getting better at the Linux side of things. I can get by but I am aware that there is much that I don’t know and could learn much better from someone who’s expert at using it rather than hunting around myself to work out how to do things. There are people who run TexGen on the HPC system so I would like to be able to support them better.

I’m looking forward to becoming part of the RSE community and learning from the other members.

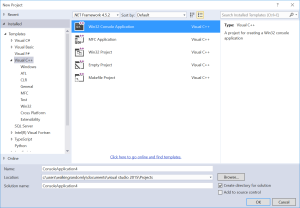

The University of Sheffield recently purchased licenses for the Windows version of the Intel compiler suite and I’m involved in the release to campus process. As part of this, I wrote some basic documentation on how to compile Hello World using the Intel C++ Compiler within Visual Studio Community Edition 2015. Since this may be useful to people outside of University of Sheffield, I reproduce this part of our documentation here.

These notes were prepared using Intel C++ XE 2015 version 15.0.6 and Visual Studio Community Edition 2015 RTM version. Note that there are problems with using this version of Intel C++ and later versions of Visual Studio Community Edition.

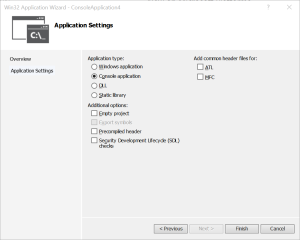

Click on any of the images to see them full size.

- Launch Visual Studio and click on File->New Project

- Choose Visual C++ -> Win32 Console Application and give your project a name.

- In the Win32 Application wizard, untick Precompiled header and Security Development Lifecycle (SDL) checks and click Finish.

- A skeleton main() function will appear. Modify the code so that it reads

#include

int main()

{

std::cout << "Hello World";

return 0;

}

- Click on Project->HelloWorld Properties and under the C++ -> General section, ensure that Suppress Startup Banner is set to No and click OK. This will ensure that when you compile, you’ll be able to see that it’s the Intel Compiler doing the work rather than Visual Studio C++.

- Click on Project->Intel Compiler->Use Intel C++

- Build and run the code by pressing CTRL F5. You should see something like the following

>------ Build started: Project: HelloWorld, Configuration: Debug Win32 ------ 1> icl /Qvc14 "/Qlocation,link,C:\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft Visual Studio 14.0\VC\bin" /ZI /W3 /Od /Qftz- -D __INTEL_COMPILER=1500 -D WIN32 -D _DEBUG -D _CONSOLE -D _UNICODE -D UNICODE /EHsc /RTC1 /MDd /GS /Zc:wchar_t /Zc:forScope /FoDebug\ /FdDebug\vc140.pdb /Gd /TP HelloWorld.cpp stdafx.cpp 1> 1> Intel(R) C++ Compiler XE for applications running on IA-32, Version 15.0.6.285 Build 20151119 1> Copyright (C) 1985-2015 Intel Corporation. All rights reserved.

Once the compilation has completed, a console window should pop up showing the Hello World output.

I recently tried to use the XE 2015 Update 6 version of the Intel C++ compiler with Visual Studio Community Edition 2015 Update 1. Even a simple Hello World console application didn’t work. I got lots of compilation errors that looked like this

1>C:\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft Visual Studio 14.0\VC\include\exception(248): error : expected an attribute name 1> [[noreturn]] _CRTIMP2_PURE void __CLRCALL_PURE_OR_CDECL __ExceptionPtrRethrow(_In_ const void*); 1> ^

There are two solutions to this problem.

- Solution 1. Downgrade Visual Studio Community Edition 2015 to the RTM version. The way I did this was to uninstall the Update 1 version and then install the RTM version using the .iso file at https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=48146 (Thanks to the Visual Studio twitter team for this link!)

- Solution 2. Upgrade the Intel C++ Compiler to XE 2016.

Getting academic credit for impactful software

The topic of this year’s Software Sustainability Institute Collaborations Workshop is Software and Credit where luminaries from the Research Software Engineering world will get together and examine the problem of getting academic credit for the development of software. An example of the problem at hand is the story of Michael Double and BoneJ. Quoting from the SSI’s Software and Credit article:

Michael Double of the Royal Veterinary College, London (RVC) is the lead on the BoneJ project, his 2010 paper describing BoneJ is the mostly highly cited paper at the RVC gaining 2 new citations per week on average(!). However it was not deemed the right shape to submit to the UK Research Evaluation Framework committee by the RVC management even though they admitted it was highly impactful.

It’s a huge problem! Software is essential for modern research but developing it isn’t often recognised as a valid research output. If developers of highly impactful software such as BoneJ struggle, what hope is there for those of us who are rather lower in the research software food chain?

Embarrassing rash? The code doctor will see you now!

When I attend these annual collaboration workshops I find that my imposter syndrome, a feeling that’s always lurking under the surface of my psyche, starts to reach a kind of fever pitch. I feel like a country-bumpkin doctor who suddenly finds himself thrust into an advanced medical research conference. Surrounded by specialist developers of new drugs, surgical techniques and high-tech scanning machines, I’m just the guy who applies ointment to patient’s embarrassing rashes.

My path to Research Software Engineer has been via the IT support route where I’ve had many job titles throughout a career defined by restructure after painful restructure. Whatever my job title was, my role has always been the same — Researchers come to me with their code problems and I do my best to solve them (or convince them that they really want a different but equivalent problem solved).

These problems include things like:-

- My code is too slow! Like 10,000 times too slow. Can you help?

- My code sometimes explodes spectacularly, can you help? It’s 10,000 lines of VBA…..with some Fortran thrown in for luck.

- How do I get my code to run on the supercomputer? Why isn’t it faster when it’s finally on it? What’s Linux?

- Um…Our paper says the answer is 0.435 but the current version of our code, the one on Bob’s pendrive, says its 3.6 Billion. Can you help us reproduce our own results?

- How the hell do you do <insert task here> in <insert inappropriate technology here>

- People keep talking about code but all I’ve ever needed is this spreadsheet. How do I make my spreadsheet do <insert thing that REALLY needs to be done some other way>. I’m a Prof who’s best friends with your boss — your answer had better be spreadsheet-y!

- I can’t code, can you help?

- We’ve got code written in <old technology> but now we want it in <new technology>, can you help?

- We do our research in <insert expensively licensed software> and now need to run it 1000s of times simultaneously. This will cost more than the GDP of China. Can you help?

- Our research is based on this thing that’s a Fortran 77 kernel wrapped in MATLAB that’s been wrapped in Perl that we call from Python. It’s been in development for over 10 years and the computer it worked on has died. We are struggling to get it working on our new machine…can you help?

- We wrote some experimental code and it worked. REALLY well! We’ve now got lots of users and suggestions for improvements but have no process to deal with all of this. Can you help?

…and so it goes on. I work with researchers from almost every field of study and at every career stage — from Undergraduate project student through to professor and everything in between. The role is something like a mix of IT support, sysadmin, software developer, teacher, consultant, alpine guide and therapist.

It’s hard, dirty work and I love it!

Doing the job that’s put in front of you

Like many of my Research Software Engineer colleagues I have Opinions (capitalisation intended! They are strong but weakly held!) on the way things should ideally be done in research software development. These opinions have been formed from years of working in the trenches, observing the trouble people get themselves into and what’s required to get them out of it. They’ve also been informed by listening to the latest research on good practice from masters of the field.

Just as your local doctor might prescribe a healthy diet, exercise and cutting down on alcohol, I prescribe things such as version control, automation and making your code open. Despite knowing all of this advice, of course, many choose to ignore it for one reason or another and get themselves in a bit of a pickle.

One of the reasons I am so proud of the United Kingdom’s National Health Service is that no matter what you’ve done to yourself, no matter how rich or poor you are, no matter how much advice you’ve ignored, their fantastic doctors and nurses will fix you. Sure, they wish that the world was a better place and that people would take better care of themselves but, ultimately, they’ll do the job that’s put in front of them — not the one they wish they had!

I guess that when I do my job, I try to emulate this behaviour.

But where’s the impact?

You’ll not find my name on any research papers and I don’t have a big project such as BoneJ to stand behind. It is exceedingly difficult to demonstrate impact, in the accepted academic sense of the word, of roles like this but I am convinced that they are vital part of the research community.

One ‘solution’ would be to only offer my services to those who have already sipped from the Research Software Engineering Kool-Aid. Now that I have my RSE fellowship to stand behind, I could easily take this route and only focus on helping projects that smell a certain way…the right way. I could work on projects that have RSE time costed in from the beginning, using only the finest, freshest ingredients and released in ways that make it easy to demonstrate impact.

This route is very tempting! I could use only the technologies I love and work in an environment where my contributions were recognised at every level — funding bodies and promotion panels in particular. Thanks to the efforts of organisations such as the software sustainability institute, I believe that developers of quality projects such as BoneJ will eventually get the recognition they deserve. By focusing on such quality, high profile projects, my career would be assured!

To my mind, however, this is akin to the NHS only providing its services to rich, well-informed patients who take heed of all the good advice leaving the rest of us to suffer.

So…I’m probably not going to do that

The Accident and Emergency of Research Software Engineering

Over time, I have come to think of my particular style of work as the accident and emergency of Research Software Engineering. It’s usually unglamorous work with little hope of formal recognition and the threat of cuts (or being reassigned to printer support!) hangs over your head every day. As anyone who’s desperately needed their services at 3am can attest, however, an A+E department is exceedingly impactful!

Despite the success of the Research Software Engineering idea, I believe that the need for the A+E type of work will increase over time along along with the percentage of researchers who need to write at least a little code. This tweet from Southampton University’s Ian Hawke, quoting Software Carpentry’s Greg Wilson, summarises my thoughts on this matter perfectly.

Here we go with @gvwilson : the gulf between the computing scientific “elite” and those emailing spreadsheets is growing, and that’s bad.

— Ian Hawke (@IanHawke) November 10, 2015

This observation closely matches my own experiences from the front-line of RSE support. Part of the role of practitioners such as me is to help close that gap by raising the game of those who email spreadsheets. I feel that I’m making progress in this area although I often wish I had more staff!

Another part of the role is to figure out how to get credit and demonstrate impact for this kind of work or we’ll risk losing it in the next round of cuts. I’m struggling with that aspect to be honest!

If you feel that your work has elements of an Accident + Emergency Research Software Engineer in it, feel free to speak up in the comments.

A couple of weeks ago, a small group of us hit on the idea of running research programming tutorials in a cafe. The ‘plan’ was that we’d develop some self-paced programming tutorial material, take over a section of the main campus Cafe (Coffee Revolution) for a couple of hours in the evening and invite some researchers to come and learn something new for free.

For our first session, we chose to do a very gentle introduction to R. The students worked through the material, which started right at the beginning with installing R and RStudio, while a group of volunteer facilitators walked the room answering questions, solving problems and forming collaborations.

I can’t stress the importance of the facilitators enough! There is no chance that this format would have worked well without a group of skilled facilitators. On the day, I was joined by

- Research Software Engineer, David Jones

- PhD Student, Claire Green

- Post Doc, Will Furnass

I also had support of a few other people in the development stages. Thanks so much to all!

It was a lot of fun to do and student feedback has been fantastic! My favourite comment came from a medical doctor who said ‘I had no idea about computer programming and I don’t think I would be brave enough to try it on my own. Yesterday, I realised that R can be something useful and not really hard to learn.’

I find interactions like this to be hugely motivational!

There was a real buzz in the room, everyone seemed to learn something useful and I walked away from the evening with a couple of interesting follow-up collaborations in the bag. There were lots of calls for future sessions on topics ranging from more advanced R through to Python, MATLAB, Mathematica and High Performance Computing. The self-paced, flipped-classroom style of teaching was also a great hit!

So, that’s what went right. What about what went wrong?

Installation Problems

We deliberately allowed time for the installation of R in the session. Ensuring that the attendees had a working install of R and RStudio on their own kit was part of the point. Before the session, I did trial installs on Windows and Mac and everything went without a hitch. Other members of the team tried fresh installs on Linux.

“Installation’s going to be a doddle…no worries” I thought.

The very first attendee who called me over for help couldn’t get RStudio started on her Mac. It crapped out with an error message I’d never seen before. A bit of googling determined that it was because she had several old versions of R already installed and RStudio took exception to this.

We also had Linux users of various flavours and most of them had problems. A user of Arch Linux gave up on trying to install RStudio and used the command line instead. One linux user called me over after he started installing the ggplot2 package asking ‘This has been compiling for ages, is that normal?’ Fortunately, we were in a cafe so he could go get himself a brew while waiting.

Some people already had versions of R and RStudio installed from waaaaay back and so didn’t feel it necessary to upgrade to the latest versions. These people discovered that they couldn’t install packages because ‘foo isn’t available for R version whatever’.

It was all rather painful to be honest! We were in full technical-support mode…but at least people left the session with working, up to date versions R and R Studio….mostly!

Power!

There wen’t many power sockets. We didn’t think much about this in advance. Ball dropped!

For a feeble attempt at a defence I’ll mention that the battery on my laptop is superb and I spend hours working in the host cafe without worrying about power. Since I’ve been so spoiled, I’ve forgotten how important a mains socket is when your battery sucks.

Next Steps

This session was an experiment — something quickly spun up to see if it might work. I’m happy to report that it did!

Our main problem is that we’ve now created demand. Demand for repeats of this session for new audiences, demand for new material and demand for further consultancy. How fortunate for us at Sheffield that we have a newly created Research Software Engineering group to help meet this demand.

Say you have two vectors in R (These are taken from my tutorial Simple nonlinear least squares curve fitting in R)

xdata = c(-2,-1.64,-1.33,-0.7,0,0.45,1.2,1.64,2.32,2.9) ydata = c(0.699369,0.700462,0.695354,1.03905,1.97389,2.41143,1.91091,0.919576,-0.730975,-1.42001)

We put these in a data frame with

data = data.frame(xdata=xdata,ydata=ydata)

This looks like this in R

xdata ydata 1 -2.00 0.699369 2 -1.64 0.700462 3 -1.33 0.695354 4 -0.70 1.039050 5 0.00 1.973890 6 0.45 2.411430 7 1.20 1.910910 8 1.64 0.919576 9 2.32 -0.730975 10 2.90 -1.420010

Exporting to a .csv file is done using the standard R function, write.csv

write.csv(data,file='example_data.csv')

The resulting .csv file looks like this:

"","xdata","ydata" "1",-2,0.699369 "2",-1.64,0.700462 "3",-1.33,0.695354 "4",-0.7,1.03905 "5",0,1.97389 "6",0.45,2.41143 "7",1.2,1.91091 "8",1.64,0.919576 "9",2.32,-0.730975 "10",2.9,-1.42001

I don’t want to include the row numbers in my output. To achieve this, we do

write.csv(data,file='example_data.csv',row.names=FALSE)

This gets us a file that looks like this:

"xdata","ydata" -2,0.699369 -1.64,0.700462 -1.33,0.695354 -0.7,1.03905 0,1.97389 0.45,2.41143 1.2,1.91091 1.64,0.919576 2.32,-0.730975 2.9,-1.42001

I can also remove the quotes around xdata and ydata with quote=FALSE

write.csv(data,file='example_data.csv',row.names=FALSE,quote=FALSE)

giving the file below

xdata,ydata -2,0.699369 -1.64,0.700462 -1.33,0.695354 -0.7,1.03905 0,1.97389 0.45,2.41143 1.2,1.91091 1.64,0.919576 2.32,-0.730975 2.9,-1.42001

Changing the separator

Despite the fact that they are asking R to write a comma separated file, some people try to change the separator. Perhaps you’d like to try changing it to a tab for example. The following looks reasonable:

write.csv(data,file='example_data.csv',row.names=FALSE,quote=FALSE,sep="\t")

Although it understands what you are trying to do, R will completely ignore your request!

Warning message: In write.csv(data, file = "example_data.csv", row.names = FALSE, : attempt to set 'sep' ignored

This is because write.csv is designed to ensure that some standard .csv conventions are followed. It’s trying to protect you against yourself!

In the UK, the convention for .csv files is to use . for a decimal point and , as a separator and that’s the convention that write.csv sticks to. Other countries have a different convention – they use a , for the decimal point and a ; for the separator. The function write.csv2 takes care of that for you.

If you absolutely must change the separator to something else, make use of write.table instead:

write.table(data,file='example_data.csv',row.names=FALSE,quote=FALSE,sep="\t")

Now, the file will come out like this:

xdata ydata -2 0.699369 -1.64 0.700462 -1.33 0.695354 -0.7 1.03905 0 1.97389 0.45 2.41143 1.2 1.91091 1.64 0.919576 2.32 -0.730975 2.9 -1.42001

Further reading: Official write.table documentation in R

I sometimes give a talk on basic research software engineering called ‘Is your research correct?’ (slides here). Near the beginning of this talk I refer to what I’ve modestly named ‘Croucher’s Law’

CROUCHER’S LAW

I CAN BE AN IDIOT AND WILL MAKE MISTAKES.

Croucher’s law has a corollary:

YOU ARE NO DIFFERENT!

The idea is that once you accept this aspect of yourself, you can start to adopt working practices to mitigate against it. In the context of programming, it includes things such as automation, version control, adopting testing and so on.

For me, this isn’t just a law for programming — it’s a law that can be applied to every aspect of life. Unlike my parents, for example, I automate the payment of my bills by using direct debit because I know I’ll eventually forget to pay something otherwise.

The genesis of Croucher’s law demonstrate’s its truth. While sat in a talk given by Jos Martin of The Mathworks, he suddenly stopped and said ‘Mike. We need to talk about Croucher’s law!’ before moving to his next slide which had the title ‘Martin’s Law’. It was very similar to ‘mine’ and it turns out that I had seen his talk years before and had subconsciously ripped him off!

The fact that I had forgotten this demonstrates to me that Croucher’s law is the stronger result :)

Other relevant posts from WalkingRandomly

- On failure – I fail all the time…and that’s OK.

- Is your research software correct?

While waiting for the rain to stop before heading home, I started messing around with the heart equation described in an old WalkingRandomly post. Playing code golf with myself, I worked to get the code tweetable. In Python:

from pylab import *

x=r_[-2:2:0.001]

show(plot((sqrt(cos(x))*cos(200*x)+sqrt(abs(x))-0.7)*(4-x*x)**0.01)) pic.twitter.com/gbOTbYSaIG— Mike Croucher (@walkingrandomly) February 8, 2016

In R:

x=seq(-2,2,0.001)

y=Re((sqrt(cos(x))*cos(200*x)+sqrt(abs(x))-0.7)*(4-x*x)^0.01)

plot(x,y)#rstats pic.twitter.com/trpgEnNna4— Mike Croucher (@walkingrandomly) February 8, 2016

I liked the look of the default plot in R so animated it by turning 200 into a parameter that ranged from 1 to 200. The result was this animation:

Finding this animation based on previous tweets oddly mesmerising #rstats pic.twitter.com/e3q6lZqWcP

— Mike Croucher (@walkingrandomly) February 8, 2016

The code for the above isn’t quite tweetable:

options(warn=-1)

for(num in seq(1,200,1))

{

filename = paste("rplot" ,sprintf("%03d", num),'.jpg',sep='')

jpeg(filename)

x=seq(-2,2,0.001)

y=Re((sqrt(cos(x))*cos(num*x)+sqrt(abs(x))-0.7)*(4-x*x)^0.01)

plot(x,y,axes=FALSE,ann=FALSE)

dev.off()

}

This produces a lot of .jpg files which I turned into the animated gif with ImageMagick:

convert -delay 12 -layers OptimizeTransparency -colors 8 -loop 0 *.jpg animated.gif

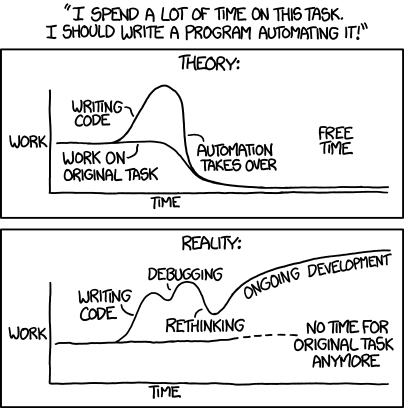

John D Cook published a great article on automation recently. He discusses the commonly-held idea that the primary reason to automate things is to save time. As anyone who’s actually gone through this process will tell you, this strategy can often backfire and John points to a comic from the ever-wonderful xkcd that illustrates this perfectly.

John suggests that another reason to automate is to save mental energy rather than time and I completely agree! This is a great reason to automate. When you are under pressure to complete a task that has to be done right first time, being able to simply push the big red button and KNOW that it will work is worth a great deal.

Automation as knowledge storage and transfer

Another use of automation is as a way to store and transfer the knowledge of how to get things done.

I work with a huge array of technologies, spending a large part of my working day poring through manuals, documentation, textbooks and google searches figuring out how to do some task, foo. By the end of the project, I’ll be an expert at doing foo but I know that this expertise won’t last. I’ll soon be moving onto the next project, the next set of technologies and my hard-won knowledge will leak from my brain-cache as quickly as it was filled.

I often find that the fastest way to distill my knowledge of how to do something is to write a script that automates it. It’s often more concise and quicker to write than documentation and is usually useful to me and possibly others. It also serves as a great launching point for relearning the material if ever I revisit this particular set of technologies and tasks.

Automate to improve your processes

Having an automated script also allows others to easily reproduce what I have done. You want what I have? Run this thing and it’s yours. A favour from me to you!

Initially, this looks and feels like an act of pure altruism. I put in a large amount of hard work and someone else benefits. In my experience, however, payback always comes my way when those who use my work give me feedback on how to do it better.

Way back in 2008, I wrote a few blog posts about using mathematical software to generate christmas cards:

- Mathematical Christmas Cards – Walking Randomly Christmas Challenge

- A MATLAB Christmas card

- Christmas geetings – SAGE style

I’ve started moving the code from these to a github repository. If you’ve never contributed to an open source project before and want some practice using git or github, feel free to write some code for a christmas message along similar lines and submit a Pull Request.